Heaven Sword and Dragon Sabre Read Online

| Katana ( 刀 ) | |

|---|---|

A katana modified from a tachi forged by Motoshige. Bizen Osafune schoolhouse influenced by the Sōshū school. 14th century, Nanboku-chō period. Important Cultural Property. Tokyo National Museum. | |

| Type | Sword |

| Place of origin | Japan |

| Service history | |

| Used past | Samurai, Onna-musha, Ninja, Kendo, Iaido practitioners |

| Product history | |

| Produced | Nanboku-chō flow (1336-1392) which corresponds to the early Muromachi period (1336–1573)[1] to present |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 1.1–1.five kg |

| Blade length | Approx. 60–80 cm (23.62–31.5 in) |

| | |

| Blade blazon | Curved, single-edged |

| Hilt blazon | Two-handed swept, with circular or squared guard |

| Scabbard/sheath | Lacquered woods, some are covered with fish skin, decorated with contumely and copper.[2] [3] |

A katana ( 刀 or かたな or カタナ ) is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a round or squared guard and long grip to arrange 2 hands. Developed later than the tachi, it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge facing upward. Since the Muromachi period, many old tachi were cutting from the root and shortened, and the blade at the root was crushed and converted into katana.[four] The official term for katana in Japan is uchigatana (打刀) and the term katana (刀) ofttimes refers to single-edged swords from effectually the earth.[5]

Etymology and loanwords [edit]

The word katana first appears in Japanese in the Nihon Shoki of 720. The term is a compound of kata ("i side, one-sided") + na ("blade"),[6] [7] [8] in contrast to the double-sided tsurugi. Encounter more than at the Wiktionary entry.

The katana belongs to the nihontō family unit of swords, and is distinguished by a blade length (nagasa) of more than than 2 shaku, approximately 60 cm (24 in).[ix]

Katana can also exist known as dai or daitō amongst Western sword enthusiasts, although daitō is a generic proper noun for any Japanese long sword, literally meaning "big sword".[10]

As Japanese does non have carve up plural and singular forms, both katanas and katana are considered acceptable forms in English.[xi]

Pronounced [katana], the kun'yomi (Japanese reading) of the kanji 刀, originally significant unmarried edged blade (of whatever length) in Chinese, the give-and-take has been adopted equally a loanword by the Portuguese.[12] In Portuguese the designation (spelled catana) means "large pocketknife" or machete.[12]

Description [edit]

Mei (signature) and Nakago (tang) of an Edo period katana

The katana is generally defined as the standard sized, moderately curved (as opposed to the older tachi featuring more than curvature) Japanese sword with a blade length greater than 60.6 cm (23.86 inches) (Japanese 2 Shaku).[13] It is characterized by its distinctive appearance: a curved, slender, unmarried-edged blade with a round or squared guard (tsuba) and long grip to accommodate 2 hands.[13]

With a few exceptions, katana and tachi can be distinguished from each other, if signed, by the location of the signature (mei) on the tang (nakago). In general, the mei should be carved into the side of the nakago which would face outward when the sword was worn. Since a tachi was worn with the cutting border down, and the katana was worn with the cutting edge upward, the mei would be in opposite locations on the tang.[14]

Western historians have said that katana were among the finest cutting weapons in world military history.[15] [16] However, the main weapons on the battlefield in the Sengoku period in the 15th century were yumi (bow), yari (spear) and tanegashima (gun), and katana and tachi were used only for close gainsay. During this menses, the tactics changed to a grouping boxing by ashigaru (foot soldiers) mobilized in large numbers, and so naginata (pole weapon) and tachi became obsolete as weapons on the battleground and were replaced past yari and katana.[17] [18] [19] In the relatively peaceful Edo menses, katana increased in importance as a weapon, and at the end of the Edo menstruum, shishi (political activists) fought many battles using katana equally their main weapon. Throughout history, katana and tachi were oft used equally gifts between daimyo (feudal lord) and samurai, or as offerings to the kami enshrined in Shinto shrines, and symbols of authority and spirituality of samurai.[xviii] [xx] [19] [17]

History [edit]

The production of swords in Japan is divided into specific time periods:[21]

- Jōkotō (ancient swords, until around 900)

- Kotō (erstwhile swords from effectually 900–1596)

- Shintō (new swords 1596–1780)

- Shinshintō (newer swords 1781–1876)

- Gendaitō (modern or gimmicky swords 1876–present)

Kotō (Old swords) [edit]

Masamune forges a katana with an assistant (ukiyo-e)

A Sōshū school katana modified from a tachi forged by Masamune. As it was owned by Ishida Mitsunari, it was commonly called Ishida Masamune. Important Cultural Belongings. Tokyo National Museum

Katana originates from sasuga (刺刀), a kind of tantō (short sword or knife) used past lower-ranking samurai who fought on pes in the Kamakura period (1185–1333). Their main weapon was a long naginata and sasuga was a spare weapon. In the Nanboku-chō period (1336-1392) which corresponds to the early Muromachi period (1336-1573), long weapons such as ōdachi were popular, and along with this, sasuga lengthened and finally became katana.[22] [23] Also, there is a theory that koshigatana (腰刀), a kind of tantō which was equipped by high ranking samurai together with tachi, adult to katana through the same historical background as sasuga, and it is possible that both developed to katana.[24] The oldest katana in existence today is called Hishizukuri uchigatana, which was forged in the Nanbokuchō period, and was dedicated to Kasuga Shrine later.[i]

The showtime utilise of katana as a discussion to describe a long sword that was dissimilar from a tachi, occurs equally early on as the Kamakura Period.[13] These references to "uchigatana" and "tsubagatana" seem to point a different style of sword, mayhap a less costly sword for lower-ranking warriors. Starting around the twelvemonth 1400, long swords signed with the katana-style mei were made. This was in response to samurai wearing their tachi in what is at present called "katana style" (cut edge upward). Japanese swords are traditionally worn with the mei facing abroad from the wearer. When a tachi was worn in the mode of a katana, with the cutting edge up, the tachi's signature would be facing the wrong way. The fact that swordsmiths started signing swords with a katana signature shows that some samurai of that fourth dimension flow had started wearing their swords in a dissimilar style.[25] [26]

Traditionally, yumi (bows) were the master weapon of war in Japan, and tachi and naginata were used just for close combat. The Ōnin State of war in the belatedly 15th century in the Muromachi catamenia expanded into a large-scale domestic war, in which employed farmers called ashigaru were mobilized in large numbers. They fought on human foot using katana shorter than tachi. In the Sengoku period (flow of warring states) in the belatedly Muromachi period, the state of war became bigger and ashigaru fought in a close formation using yari (spears) lent to them. Furthermore, in the late 16th century, tanegashima (muskets) were introduced from Portugal, and Japanese swordsmiths mass-produced improved products, with ashigaru fighting with leased guns. On the battlefield in Japan, guns and spears became primary weapons in addition to bows. Due to the changes in fighting styles in these wars, the tachi and naginata became obsolete among samurai, and the katana, which was like shooting fish in a barrel to carry, became the mainstream. The dazzling looking tachi gradually became a symbol of the authorization of loftier-ranking samurai.[22] [xx] [19]

On the other hand, kenjutsu (swordsmanship) that makes apply of the characteristics of katana was invented. The quicker draw of the sword was well suited to combat where victory depended heavily on short response times. (The practice and martial art for drawing the sword quickly and responding to a sudden attack was called Battōjutsu, which is notwithstanding kept alive through the education of Iaido.) The katana further facilitated this past existence worn thrust through a belt-like sash (obi) with the sharpened edge facing up. Ideally, samurai could draw the sword and strike the enemy in a single motion. Previously, the curved tachi had been worn with the edge of the blade facing down and suspended from a belt.[13] [27]

From the 15th century, low-quality swords were mass-produced under the influence of the big-calibration war. These swords, along with spears, were lent to recruited farmers called ashigaru and swords were exported. Such mass-produced swords are called kazuuchimono, and swordsmiths of the Bisen school and Mino school produced them by division of labor.[22] [28] The export of katana and tachi reached its pinnacle during this period, from the belatedly 15th century to early on 16th century when at least 200,000 swords were shipped to Ming Dynasty Red china in official merchandise in an attempt to soak up the production of Japanese weapons and get in harder for pirates in the expanse to arm. In the Ming Dynasty of China, Japanese swords and their tactics were studied to repel pirates, and wodao and miaodao were developed based on Japanese swords.[2] [29] [30]

From this flow, the tang (nakago) of many one-time tachi were cut and shortened into katana. This kind of remake is called suriage (磨上げ).[4] For example, many of the tachi that Masamune forged during the Kamakura catamenia were converted into katana, so his only existing works are katana and tantō.[31]

From the late Muromachi period (Sengoku menstruum) to the early Edo period, samurai were sometimes equipped with a katana blade pointing downwards like a tachi. This way of sword is chosen handachi, "half tachi". In handachi, both styles were often mixed, for example, fastening to the obi was katana mode, but metalworking of the scabbard was tachi style.[32]

In the Muromachi period, peculiarly the Sengoku period, people such every bit farmers, townspeople, and monks could accept a sword. Still, in 1588 Toyotomi Hideyoshi banned farmers from owning weapons and conducted a sword hunt to forcibly remove swords from anyone identifying as a farmer.[24]

The length of the katana blade varied considerably during the course of its history. In the late 14th and early 15th centuries, katana blades tended to have lengths betwixt seventy and 73 centimetres (28 and 29 in). During the early on 16th century, the boilerplate length dropped about 10 centimetres (3.9 in), approaching closer to 60 centimetres (24 in). By the late 16th century, the average length had increased again by virtually 13 centimetres (5.1 in), returning to approximately 73 centimetres (29 in).[27]

Shintō (New swords) [edit]

Antique Japanese daishō, the traditional pairing of ii Japanese swords which were the symbol of the samurai, showing the traditional Japanese sword cases (koshirae) and the divergence in size betwixt the katana (bottom) and the smaller wakizashi (acme).

Swords forged after 1596 in the Keichō period of the Azuchi–Momoyama period are classified as shintō (New swords). Japanese swords later shintō are dissimilar from kotō in forging method and steel (tamahagane). This is idea to exist because Bizen school, which was the largest swordsmith group of Japanese swords, was destroyed past a nifty alluvion in 1590 and the mainstream shifted to Mino school, and because Toyotomi Hideyoshi virtually unified Japan, uniform steel began to exist distributed throughout Nihon. The kotō swords, especially the Bizen school swords fabricated in the Kamakura period, had a midare-utsuri similar a white mist between hamon and shinogi, just in the swords afterward shintō it has well-nigh disappeared. In addition, the whole body of the blade became whitish and hard. Most no one was able to reproduce midare-utsurii until Kunihira Kawachi reproduced it in 2014.[33] [34]

Sword fittings. Tsuba (top left) and fuchigashira (top right) fabricated by Ishiguro Masayoshi in the 18th or 19th century. Kogai (middle) and kozuka (bottom) made by Yanagawa Naomasa in the 18th century, Edo period. Tokyo Fuji Art Museum.

As the Sengoku period (period of warring states) ended and the Azuchi-Momoyama flow to the Edo period started, katana-forging besides developed into a highly intricate and well-respected art form. Lacquered saya (scabbards), ornate engraved fittings, silk handles and elegant tsuba (handguards) were pop among samurai in the Edo Period, and eventually (particularly when Japan was in peace time), katana became more than cosmetic and ceremonial items than applied weapons.[35] The Umetada schoolhouse led by Umetada Myoju who was considered to exist the founder of shinto led the improvement of the artistry of Japanese swords in this menstruation. They were both swordsmiths and metalsmiths, and were famous for etching the bract, making metallic accouterments such as tsuba (handguard), remodeling from tachi to katana (suriage), and inscriptions inlaid with aureate.[36]

During this period, the Tokugawa shogunate required samurai to article of clothing Katana and shorter swords in pairs. These short swords were wakizashi and tantō, and wakizashi were mainly selected. This ready of 2 is chosen a daishō. Merely samurai could article of clothing the daishō: it represented their social power and personal honour.[13] [27] [37] Samurai could wear decorative sword mountings in their daily lives, but the Tokugawa shogunate regulated the formal sword that samurai wore when visiting a castle by regulating it as a daisho fabricated of a black scabbard, a hilt wrapped with white ray peel and black string.[38] Japanese swords made in this period are classified as shintō.[39]

Shinshintō (New new swords) [edit]

Daishō (Katana and Wakizashi) forged by Minamoto no Kiyomaro. 1848, Belatedly Edo flow. (not to scale)

Daishō for formal attire with black scabbard, hilt winding thread and white ray peel hilt, which were regulated by the Tokugawa Shogunate. Daishō owned by Uesugi association. Late Edo flow.

In the belatedly 18th century, swordsmith Suishinshi Masahide criticized that the present katana blades only emphasized decoration and had a trouble with their toughness. He insisted that the bold and strong kotō blade from the Kamakura period to the Nanboku-chō menses was the ideal Japanese sword, and started a movement to restore the product method and apply information technology to Katana. Katana made afterwards this is classified as a shinshintō.[39] One of the most popular swordsmiths in Japan today is Minamoto Kiyomaro who was active in this shinshintō flow. His popularity is due to his timeless exceptional skill, as he was nicknamed "Masamune in Yotsuya" after his disastrous life. His works were traded at high prices and exhibitions were held at museums all over Nihon from 2013 to 2014.[forty] [41] [42]

The idea that the blade of a sword in the Kamakura catamenia is the best has been continued until now, and as of the 21st century, 80% of Japanese swords designated as National treasure in Nihon were made in the Kamakura period, and 70% of them were tachi.[43] [44]

The arrival of Matthew Perry in 1853 and the subsequent Convention of Kanagawa caused chaos in Japanese social club. Conflicts began to occur frequently between the forces of sonnō jōi (尊王攘夷派), who wanted to overthrow the Tokugawa Shogunate and rule by the Emperor, and the forces of sabaku (佐幕派), who wanted the Tokugawa Shogunate to go along. These political activists, called the shishi (志士), fought using a practical katana, called the kinnōtō (勤皇刀) or the bakumatsutō (幕末刀). Their katana were often longer than 90 cm (35.43 in) in bract length, less curved, and had a big and sharp betoken, which was advantageous for stabbing in indoor battles.[39]

Gendaitō (Modernistic or contemporary swords) [edit]

Meiji – Globe State of war Ii [edit]

Although the number of forged swords decreased in the Meiji period, many artistically excellent mountings were made. A wakizashi forged by Soshu Akihiro. Nanboku-chō menstruation. (summit) Wakizashi mounting, Early on Meiji period. (bottom)

During the Meiji catamenia, the samurai class was gradually disbanded, and the special privileges granted to them were taken away, including the right to conduct swords in public. The Haitōrei Edict in 1876 forbade the carrying of swords in public except for certain individuals, such equally former samurai lords (daimyō), the military, and the police.[45] Skilled swordsmiths had problem making a living during this period as Japan modernized its armed services, and many swordsmiths started making other items, such every bit farm equipment, tools, and cutlery. The craft of making swords was kept alive through the efforts of some individuals, notably Miyamoto Kanenori (宮本包則, 1830–1926) and Gassan Sadakazu (月山貞一, 1836–1918), who were appointed Purple Household Artist. The man of affairs Mitsumura Toshimo (光村利藻, 1877-1955)tried to preserve their skills by ordering swords and sword mountings from the swordsmiths and craftsmen. He was especially enthusiastic well-nigh collecting sword mountings, and he collected near 3,000 precious sword mountings from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji flow. About 1200 items from a part of his collection are now in the Nezu Museum.[46] [47] [48]

Military action by Japan in China and Russian federation during the Meiji menses helped revive interest in swords, but it was not until the Shōwa period that swords were produced on a large calibration once more.[49] Japanese military machine swords produced betwixt 1875 and 1945 are referred to as guntō (military swords).[50]

During the pre-World War II military buildup, and throughout the war, all Japanese officers were required to habiliment a sword. Traditionally fabricated swords were produced during this period, but in social club to supply such large numbers of swords, blacksmiths with picayune or no knowledge of traditional Japanese sword industry were recruited. In add-on, supplies of the Japanese steel (tamahagane) used for swordmaking were express, then several other types of steel were also used. Quicker methods of forging were also used, such equally the use of power hammers, and quenching the bract in oil, rather than hand forging and h2o. The non-traditionally made swords from this period are chosen shōwatō, after the regnal name of the Emperor Hirohito, and in 1937, the Japanese regime started requiring the apply of special stamps on the tang (nakago) to distinguish these swords from traditionally made swords. During this menses of war, older antique swords were remounted for use in military mounts. Shortly, in Japan, shōwatō are not considered to exist "true" Japanese swords, and they can exist confiscated. Outside Nippon, however, they are collected as historical artifacts.[45] [49] [51]

Post-Earth State of war II [edit]

Japanese girl practicing iaidō with a modernistic training katana or iaitō. This sword was custom-made in Japan to suit the weight and size of the pupil. The blade is made of aluminum blend and lacks a sharp border for prophylactic reasons.

Between 1945 and 1953, sword manufacture and sword-related martial arts were banned in Japan. Many swords were confiscated and destroyed, and swordsmiths were not able to make a living. Since 1953, Japanese swordsmiths take been allowed to work, but with severe restrictions: swordsmiths must be licensed and serve a five-twelvemonth apprenticeship, and only licensed swordsmiths are allowed to produce Japanese swords (nihonto), merely two longswords per month are allowed to be produced by each swordsmith, and all swords must be registered with the Japanese Government.[52]

Outside Japan, some of the mod katanas being produced by western swordsmiths use modern steel alloys, such as L6 and A2. These modern swords replicate the size and shape of the Japanese katana and are used by martial artists for iaidō and even for cutting practice (tameshigiri).

Mass-produced swords including iaitō and shinken in the shape of katana are available from many countries, though China dominates the market.[53] These types of swords are typically mass-produced and made with a wide diversity of steels and methods.

According to the Parliamentary Clan for the Preservation and Promotion of Japanese Swords, organized by Japanese Nutrition members, many katana distributed effectually the world every bit of the 21st century are fake Japanese swords made in China. The Sankei Shimbun analyzed that this is because the Japanese authorities allowed swordsmiths to make only 24 Japanese swords per person per yr in order to maintain the quality of Japanese swords.[54] [55]

Many swordsmiths after the Edo period have tried to reproduce the sword of the Kamakura period which is considered as the best sword in the history of Japanese swords, but they have failed. And so, in 2014, Kunihira Kawachi succeeded in reproducing it and won the Masamune Prize, the highest honour as a swordsmith. No one could win the Masamune Prize unless he fabricated an extraordinary accomplishment, and in the section of tachi and katana, no i had won for 18 years before Kawauchi.[34]

Types [edit]

Katana are distinguished past their type of blade:

- Shinogi-Zukuri is the most common blade shape for Japanese katana that provides both speed and cut power. It features a distinct yokote: a line or bevel that separates the finish of the main blade and the finish of the tip. Shinogi-zukuri was originally produced afterward the Heian period.

- Shobu-Zukuri is a variation of shinogi-zukuri without a yokote, the singled-out angle betwixt the long cutting edge and the bespeak section. Instead, the edge curves smoothly and uninterrupted into the point.

- Kissaki-Moroha-Zukuri is a katana blade shape with a distinctive curved and double-edged blade. One edge of the bract is shaped in normal katana mode while the tip is symmetrical and both edges of the blade are sharp.

Forging and construction [edit]

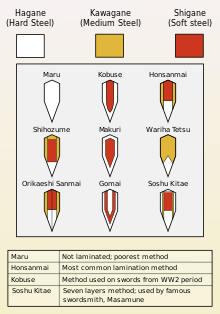

Cross sections of Japanese sword blade lamination methods

Typical features of Japanese swords represented by katana and tachi are a three-dimensional cross-sectional shape of an elongated pentagonal to hexagonal blade called shinogi-zukuri, a style in which the blade and the tang (nakago) are integrated and fixed to the hilt (tsuka) with a pivot called mekugi, and a gentle curve. When a shinogi-zukuri sword is viewed from the side, in that location is a ridge line of the thickest part of the bract called shinogi between the cut-edge side and the back side. This shinogi contributes to lightening and toughening of the bract and high cutting ability.[56]

Katana are traditionally made from a specialized Japanese steel called tamahagane,[57] which is created from a traditional smelting process that results in several, layered steels with different carbon concentrations.[58] This process helps remove impurities and fifty-fifty out the carbon content of the steel. The historic period of the steel plays a role in the ability to remove impurities, with older steel having a higher oxygen concentration, existence more easily stretched and rid of impurities during hammering, resulting in a stronger blade.[59] The smith begins by folding and welding pieces of the steel several times to work out most of the differences in the steel. The resulting block of steel is then drawn out to form a billet.

At this stage, it is only slightly curved or may take no curve at all. The katana's gentle curvature is attained by a process of differential hardening or differential quenching: the smith coats the blade with several layers of a wet clay slurry, which is a special concoction unique to each sword maker, but by and large composed of dirt, water and any or none of ash, grinding rock powder, or rust. This process is called tsuchioki. The edge of the blade is coated with a thinner layer than the sides and spine of the sword, heated, and then quenched in water (few sword makers use oil to quench the blade). The slurry causes only the blade's edge to be hardened and likewise causes the blade to curve due to the departure in densities of the micro-structures in the steel.[27] When steel with a carbon content of 0.7% is heated beyond 750 °C, information technology enters the austenite phase. When austenite is cooled very of a sudden by quenching in water, the structure changes into martensite, which is a very difficult form of steel. When austenite is allowed to cool slowly, its structure changes into a mixture of ferrite and pearlite which is softer than martensite.[60] [61] This process also creates the singled-out line down the sides of the blade called the hamon, which is made distinct by polishing. Each hamon and each smith's fashion of hamon is distinct.[27]

After the blade is forged, information technology is and so sent to be polished. The polishing takes between ane and 3 weeks. The polisher uses a series of successively finer grains of polishing stones in a process called glazing, until the bract has a mirror stop. However, the edgeless edge of the katana is often given a matte cease to emphasize the hamon.[27]

Japanese swords are more often than not fabricated by a division of labor between six and eight craftsmen. Tosho (Toko, Katanakaji) is in charge of forging blades, togishi is in accuse of polishing blades, kinkosi (chokinshi) is in charge of making metallic fittings for sword fittings, shiroganeshi is in accuse of making habaki (brade neckband), sayashi is in accuse of making scabbards, nurishi is in charge of applying lacquer to scabbards, tsukamakishi is in charge of making hilt, and tsubashi is in charge of making tsuba (manus guard). Tosho use amateur swordsmiths equally assistants. Prior to the Muromachi period, tosho and kacchushi (armorer) used surplus metal to make tsuba, merely from the Muromachi flow onwards, specialized craftsmen began to brand tsuba. Nowadays, kinkoshi sometimes serves equally shiroganeshi and tsubashi.[62] [63]

Appreciation [edit]

Historically, katana have been regarded non only as weapons but also as works of fine art, peculiarly for loftier-quality ones. For a long fourth dimension, Japanese people have developed a unique appreciation method in which the blade is regarded every bit the core of their artful evaluation rather than the sword mountings decorated with luxurious lacquer or metallic works.[64] [65]

It is said that the following iii objects are the most noteworthy objects when appreciating a blade. The first is the overall shape referred to every bit sugata. Curvature, length, width, tip, and shape of tang of the sword are the objects for appreciation. The second is a fine blueprint on the surface of the blade, which is referred to as hada or jigane. Past repeatedly folding and forging the blade, fine patterns such as fingerprints, tree rings and bark are formed on its surface. The 3rd is hamon. Hamon is a white blueprint of the cut edge produced past quenching and tempering. The object of appreciation is the shape of hammon and the crystal particles formed at the boundary of hammon. Depending on the size of the particles, they can exist divided into two types, a nie and a nioi, which makes them expect like stars or mist. In addition to these three objects, a swordsmith signature and a file blueprint engraved on tang, and a carving inscribed on the bract, which is referred to equally horimono, are also the objects of appreciation.[64] [65]

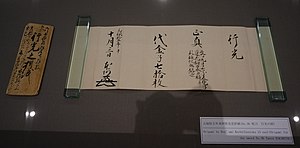

A Japanese sword authentication paper (Origami) from 1702 that Hon'ami Kōchū certified a tantō made by Yukimitsu in the 14th century equally authentic.

The Hon'ami clan, which was an authorization of appraisal of Japanese swords, rated Japanese swords from these artistic points of view. In addition, experts of modern Japanese swords judge when and by which swordsmith school the sword was made from these creative points of view.[64] [65]

Generally, the blade and the sword mounting of Japanese swords are displayed separately in museums, and this tendency is remarkable in Japan. For example, the Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum "Nagoya Touken World", one of Japan's largest sword museums, posts separate videos of the blade and the sword mounting on its official website and YouTube.[66] [67]

Rating of Japanese swords and swordsmiths [edit]

In Japan, Japanese swords are rated by regime of each menses, and some of the authority of the rating is still valid today.

In 1719, Tokugawa Yoshimune, the eighth shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate, ordered Hon'ami Kōchū, who was an dominance of sword appraisal, to record swords possessed past daimyo all over Nippon in books. In the completed "Kyōhō Meibutsu Chō" (享保名物帳) 249 precious swords were described, and additional 25 swords were described afterward. The listing as well includes 81 swords that had been destroyed in previous fires. The precious swords described in this volume were called "Meibutsu" (名物) and the criteria for pick were artistic elements, origins and legends. The list of "Meibutsu" includes 59 swords made by Masamune, 34 by Awataguchi Yoshimitsu and 22 by Go Yoshihiro, and these three swordsmiths were considered special. Daimyo hid some swords for fear that they would exist confiscated by the Tokugawa Shogunate, then even some precious swords were not listed in the book. For instance, Daihannya Nagamitsu and Yamatorige, which are now designated as National Treasures, were not listed.[43]

Katana forged by Nagasone Kotetsu. The letters inlaid with gilt on the tang (nakago) indicated that Yamano Kauemon (山野加右衛門), the official executioner of the Tokugawa shogunate and examiner of sword cut performance, cut the four human body overlapped.[68]

Yamada Asaemon V, who was the official sword cutting power examiner and executioner of the Tokugawa shogunate, published a volume "Kaiho Kenjaku" (懐宝剣尺) in 1797 in which he ranked the cutting ability of swords. The book lists 228 swordsmiths, whose forged swords are called "Wazamono" (業物) and the highest "Saijo Ō Wazamono" (最上大業物) has 12 selected. In the reprinting in 1805, 1 swordsmith was added to the highest grade, and in the major revised edition in 1830 "Kokon Kajibiko" (古今鍛冶備考), 2 swordsmiths were added to the highest grade, and in the end, fifteen swordsmiths were ranked as the highest grade. The katana forged past Nagasone Kotetsu, one of the elevation-rated swordsmith, became very popular at the time when the book was published, and many counterfeits were fabricated. In these books, the three swordsmiths treated especially in "Kyōhō Meibutsu Chō" and Muramasa, who was famous at that fourth dimension for forging swords with high cutting power, were not mentioned. The reasons for this are considered to be that Yamada was agape of challenging the authority of the shogun, that he could not employ the precious sword possessed by the daimyo in the examination, and that he was considerate of the legend of Muramasa'southward curse.[43] [69]

A katana forged by Magoroku Kanemoto. (Saijo Ō Wazamono) Belatedly Muromachi catamenia. (superlative) Katana mounting, Early on Edo period. (bottom)

At present, by the Law for the Protection of Cultural Backdrop, important swords of high historical value are designated as Important Cultural Backdrop (Jūyō Bunkazai, 重要文化財), and special swords among them are designated equally National Treasures (Kokuhō, 国宝). The swords designated every bit cultural backdrop based on the constabulary of 1930, which was already abolished, have the rank adjacent to Important Cultural Properties equally Of import Art Object (Jūyō Bijutsuhin, 重要美術品). In addition, The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords, a public involvement incorporated foundation, rates high-value swords in four grades, and the highest form Special Important Sword (Tokubetsu Juyo Token, 特別重要刀剣) is considered to be equivalent to the value of Important Fine art Object. Although swords owned by the Japanese Imperial Family are not designated as National Treasures or Of import Cultural Properties considering they are outside the jurisdiction of the Law for the Protection of Cultural Backdrop, there are many swords of the National Treasure form, and they are called "Gyobutsu" (御物).[43] [70]

Currently, there are several administrative rating systems for swordsmiths. Co-ordinate to the rating approved past the Japanese government, from 1890 to 1947, two swordsmiths who were appointed as Regal Household Artist and later 1955, six swordsmiths who were designated as Living National Treasure are regarded as the best swordsmiths. According to the rating approved by The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords, a public interest incorporated foundation, 39 swordsmiths who were designated as Mukansa (無鑑査) since 1958 are considered to be the highest ranking swordsmiths. The best sword forged past Japanese swordsmiths is awarded the most honorable Masamune prize by The Gild for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords. Since 1961, eight swordsmiths have received the Masamune Prize, and among them, three swordsmiths, Masamine Sumitani, Akitsugu Amata and Toshihira Osumi, have received the prize iii times each and Sadakazu Gassan II has received the prize two times. These four people were designated both Living National Treasures and Mukansa.[71]

Usage in martial arts [edit]

Katana were used by samurai both in the battlefield and for practicing several martial arts, and modern martial artists still employ a multifariousness of katana. Martial arts in which training with katana is used include iaijutsu, battōjutsu, iaidō, kenjutsu, kendō, ninjutsu and Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū. [72] [73] [74] However, for safety reasons, katana used for martial arts are usually blunt edged, to reduce the risk of injury. Abrupt katana are only really used during tameshigiri (blade testing), where a practitioner practices cutting a bamboo or tatami straw post.

Storage and maintenance [edit]

If mishandled in its storage or maintenance, the katana may become irreparably damaged. The blade should be stored horizontally in its sheath, curve downward and edge facing upward to maintain the edge. It is extremely important that the blade remain well-oiled, powdered and polished, as the natural moisture residue from the easily of the user will rapidly cause the blade to rust if not cleaned off. The traditional oil used is chōji oil (99% mineral oil and ane% clove oil for fragrance). Similarly, when stored for longer periods, it is important that the katana be inspected frequently and aired out if necessary in order to prevent rust or mold from forming (mold may feed off the salts in the oil used to smooth the blade).[75]

World records [edit]

Multiple sword globe records were made with a katana and verified by Guinness Globe Records. Iaido principal Isao Machii set the record for "Most martial arts katana cuts to one mat (suegiri)",[76] "Fastest 1,000 martial arts sword cuts",[77] "Most sword cuts to straw mats in iii minutes",[78] and "Fastest lawn tennis brawl (708km/h) cutting past sword".[79] There are various records for Tameshigiri. For instance the Greek Agisilaos Vesexidis set the record for most martial arts sword cuts in one minute (73) on 25 June 2016.[eighty]

Ownership and merchandise restrictions [edit]

Republic of Ireland [edit]

Under the Firearms and Offensive Weapons Act 1990 (Offensive Weapons) (Amendment) Order 2009, katanas fabricated mail service-1953 are illegal unless fabricated by hand co-ordinate to traditional methods.[81]

United Kingdom [edit]

Equally of April 2008, the British government added swords with a curved bract of 50 cm (20 in) or over in length ("the length of the blade shall be the straight line distance from the top of the handle to the tip of the blade") to the Offensive Weapons Club.[82] This ban was a response to reports that samurai swords were used in more than 80 attacks and four killings over the preceding four years.[83] Those who violate the ban would be jailed upwardly to half-dozen months and charged a fine of £5,000. Martial arts practitioners, historical re-enactors and others may still own such swords. The sword can also be legal provided information technology was made in Japan earlier 1954, or was made using traditional sword making methods. It is likewise legal to buy if it tin can be classed as a "martial artist's weapon". This ban applies to England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. This ban was amended in Baronial 2008 to permit sale and ownership without licence of "traditional" paw-forged katana.[84]

Gallery [edit]

-

A katana forged by Hizen Tadayoshi I. (Saijo Ō Wazamono) Azuchi-Momoyama period. (superlative) Katana mounting, Late Edo catamenia. (bottom)

-

Katana style sword mounting with hollyhocks design crests in maki-due east lacquer and female parent of pearl inlay on ikakeji lacuer basis. Edo period, 19th century.

-

Daishō, blackness waxed scabbards. This daishō is an breezy style because the thread wound on the hilt is purple. 19th century, Edo period. Tokyo Fuji Art Museum.

-

Mounting for a katana forged by Motoshige. late 16th or early 17th century, Azuchi–Momoyama or Edo period. Important Cultural Property. Tokyo National Museum.

-

Japanese katana showing a horimono (blade carving), Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

Hilt of katana. Early Edo flow.

-

The inscription (mei) on the tang (nakago) of a katana forged by Hizen tadayoshi I, Azuchi-Momoyama period. (top) Hilt of katana. Late Edo period. (lesser)

-

Koshirae (mountings) of an Edo period daishō, rayskin wrapped with silk.

-

Kissaki (point) of an Edo period katana.

Pop civilisation [edit]

- Katana swords are a common weapon for characters in anime and manga who fight using a sword.

- Two katana swords were the standard weapons of Leonardo in the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles franchise. One was likewise used past Miyamoto Usagi, the virtuous rabbit ronin who occasionally teamed upwards with the Ninja Turtles and became a brotherly effigy to Leonardo due to both being swordsmen and valuing honour.

- In Fist of Legend, General Fujita uses a katana every bit he tries to kill the chief hero Chen and his mentor Huo.

- In Samurai Jack, the championship character wielded a mystic katana sword.

- A katana sword was a standard weapon of Deathstroke, a mercenary from DC Comics.

- A katana sword was used by the Silverish Samurai, a samurai crime boss from Marvel Comics.

- A katana sword was used by Samurai Org in Ability Rangers Wild Force.

- A katana sword is used by Youmu Konpaku from the Touhou Projection video game series.

Encounter likewise [edit]

| | Wikimedia Eatables has media related to Katana. |

- Kenjutsu

- Iaidō

- Japanese sword mountings

- Japanese sword

- Daishō

- Ōdachi

- Tachi

- Wakizashi

- Tenka-Goken (Five Swords under Heaven) - five individual swords traditionally viewed as the best Japanese swords

- Backsword

- Broadsword

- Japanese swords in fiction

- Korean sword

References [edit]

- ^ a b Kazuhiko Inada (2020), Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords. p43. ISBN 978-4651200408

- ^ a b Takeo Tanaka. (2012) Wokou p.104. Kodansha. ISBN 978-4062920933

- ^ "日本の技術の精巧さは…". Mainichi Shimbun. 27 March 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016.

- ^ a b 日本刀鑑賞のポイント「日本刀の姿」 Nagoya Touken Museum Touken World

- ^ 日本刀と刀の違い Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken World

- ^ 1988, 国語大辞典(新装版) (Kokugo Dai Jiten, Revised Edition) (in Japanese), Tōkyō: Shogakukan, 刀 ( katana ) entry available online here

- ^ 2006, 大辞林 (Daijirin), Third Edition (in Japanese), Tōkyō: Sanseidō, ISBN iv-385-13905-ix

- ^ 1995, 大辞泉 (Daijisen) (in Japanese), Tōkyō: Shogakukan, ISBN 4-09-501211-0, 刀 ( katana ) entry available online here

- ^ "How Long Is a Katana?". Medieval Swords World. iii August 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Sun-Jin Kim (1996). Tuttle Dictionary Martial Arts Korea, People's republic of china & Nihon. Tuttle Publishing. p. 61. ISBN978-0-8048-2016-five.

- ^ Adrian Akmajian; Richard A. Demers; Ann One thousand. Farmer; Robert M. Harnish (2001). Linguistics: An Introduction to Language and Communication. Massachusetts: The MIT Press. p. 624. ISBN9780262511230.

- ^ a b Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado; Anthony X. Soares (1988). Portuguese Vocables in Asiatic Languages: From the Portuguese Original of Monsignor Sebastiao Rodolfo Dalgado. Southern asia Books. p. 520. ISBN978-81-206-0413-1.

- ^ a b c d e Kanzan Sato (1983). The Japanese Sword: A Comprehensive Guide (Japanese arts Library). Japan: Kodansha International. p. 220. ISBN978-0-87011-562-ii.

- ^ 土子民夫 (May 2002). 日本刀21世紀への挑戦. Kodansha International. p. 30. ISBN978-4-7700-2854-nine.

- ^ Roger Ford (2006). Weapon: A Visual History of Arms and Armor. DK Publishing. pp. 66, 120. ISBN9780756622107.

- ^ Anthony J. Bryant and Angus McBride (1994) Samurai 1550–1600. Osprey Publishing. p. 49. ISBN 1855323451

- ^ a b Kazuhiko Inada (2020), Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords. p42. ISBN 978-4651200408

- ^ a b 歴史人 September 2020. pp.forty-43. ASIN B08DGRWN98

- ^ a b c Arms for battle - spears, swords, bows. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken Earth

- ^ a b History of Japanese swords "Muromachi period - Azuchi-Momoyama period". Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken World

- ^ Transition of kotō, shintō, shinshintō, and gendaitō. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken World

- ^ a b c 歴史人 September 2020. p40. ASIN B08DGRWN98

- ^ Listing of terms related to Japanese swords "Sasuga". Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken World.

- ^ a b Differences in Japanese swords according to status. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken Earth.

- ^ Stephen Turnbull (8 Feb 2011). Katana: The Samurai Sword. Osprey Publishing. pp. 22–. ISBN978-1-84908-658-5.

- ^ Kōkan Nagayama (1997). The Connoisseur'due south Volume of Japanese Swords. Kodansha International. p. 28. ISBN978-4-7700-2071-0.

- ^ a b c d due east f Leon Kapp; Hiroko Kapp; Yoshindo Yoshihara (1987). The Craft of the Japanese Sword. Nippon: Kodansha International. p. 167. ISBN978-0-87011-798-5.

- ^ 歴史人 September 2020. pp.70-71. ASIN B08DGRWN98

- ^ Koichi Shinoda. (1 May 1992). Chinese Weapons and Armor. Shinkigensha. ISBN 9784883172115

- ^ Rekishi Gunzo. (2 July 2011) Consummate Works on Strategic and Tactical Weapons. From Ancient China to Modern China. Gakken. ISBN 9784056063448

- ^ 相州伝の名工「正宗」. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken World.

- ^ weblio. Handachi-Goshirae.

- ^ History of Japanese sword. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken World

- ^ a b 日本刀鑑賞のポイント「日本刀の映りとは」. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken World

- ^ Masayuki Murata. 明治工芸入門 p.120. Me no Me, 2017 ISBN 978-4907211110

- ^ 特別展「埋忠〈UMETADA〉桃山刀剣界の雄」. Internet Museum

- ^ Oscar Ratti; Adele Westbrook (1991). Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan. Tuttle Publishing. p. 484. ISBN978-0-8048-1684-7.

- ^ Kazuhiko Inada (2020), Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords. p46. ISBN 978-4651200408

- ^ a b c 歴史人 September 2020. pp.42-43. ASIN B08DGRWN98

- ^ 幕末に活躍した日本刀の名工「清麿」展=ダイナミックな切っ先、躍動感あふれる刃文. Jiji Press

- ^ 清麿展 -幕末の志士を魅了した名工- Internet Museum

- ^ 源清麿 四谷正宗の異名を持つ新々刀随一の名工. Kōgetudō.

- ^ a b c d 日本刀の格付けと歴史. Touken Globe

- ^ 鎌倉期の古名刀をついに再現 論説委員・長辻象平. Sankei Shimbun. 2 July 2017

- ^ a b Kōkan Nagayama (1997). The Connoisseur'south Book of Japanese Swords. Kodansha International. p. 43. ISBN978-four-7700-2071-0.

- ^ Tiptop of Elegance -Sword fittings of the Mitsumura Drove-. Nezu Museum

- ^ The World of Edo Dandyism From Swords to Inro. Cyberspace Museum

- ^ Superlative of Elegance -Sword fittings of the Mitsumura Collection-. Cyberspace Museum

- ^ a b Clive Sinclaire (ane November 2004). Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Lyons Printing. pp. 58–59. ISBN978-i-59228-720-8.

- ^ John Yumoto (13 December 2013). The Samurai Sword: A Handbook. Tuttle Publishing. pp. vi, 70. ISBN978-1-4629-0706-9.

- ^ Leon Kapp; Hiroko Kapp; Yoshindo Yoshihara (January 2002). Modern Japanese Swords and Swordsmiths: From 1868 to the Present. Kodansha International. pp. 58–70. ISBN978-4-7700-1962-ii.

- ^ Clive Sinclaire (1 November 2004). Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Lyons Printing. p. lx. ISBN978-i-59228-720-eight.

- ^ Steve Shackleford (7 September 2010). "Sword Capitol of the Globe". Spirit of the Sword: A Commemoration of Artistry and Craftsmanship. Iola, Wisconsin: Adams Media. p. 23. ISBN978-1-4402-1638-ane.

- ^ Sankei Shimbun, June 22, 2018. p.1

- ^ Sankei Shimbun, June 22, 2018. p.2

- ^ 歴史人 September 2020. p36, p47, p50. ASIN B08DGRWN98

- ^ 鉄と生活研究会 (2008). トコトンやさしい鉄の本. 日刊工業新聞社. ISBN978-4-526-06012-0.

- ^ Secrets of the Samurai Sword. Pbs.org. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- ^ "Step 1: Types of Katana Swords". Katana Sword Reviews. 3 September 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Richard Cohen (18 December 2007). By the Sword: A History of Gladiators, Musketeers, Samurai, Swashbucklers, and Olympic Champions. Random Firm Publishing Group. p. 124. ISBN978-0-307-43074-8.

- ^ James Drewe (15 February 2009). Tàijí Jiàn 32-Posture Sword Class. Singing Dragon. p. 10. ISBN978-1-84642-869-2.

- ^ 刀装具の名工 Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken Earth

- ^ Bizen Osafune Japanese Sword. Setouchi City, Okayama Prefecture.

- ^ a b c How to appreciate a Japanese sword. Tozando.

- ^ a b c Kazuhiko Inada (2020), Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords. pp.117-119 ISBN 978-4651200408

- ^ Touken World YouTube videos nearly Japanese swords

- ^ Touken World YouTube videos on koshirae (sword mountings)

- ^ Katana Signed Nagasone Okisato Nyudo Kotetsu. Tokyo Fuji Fine art Museum.

- ^ Iwasaki, Kosuke (1934), "Muramasa's curse (村正の祟りについて)", Japanese sword course, volume 8, Historical Anecdotes and Practical Appreciation. (日本刀講座 第8巻 歴史及説話・実用及鑑賞), Yuzankaku, pp. 91–118, doi:x.11501/1265855

- ^ <審査規程第17条第1項に基づく審査基準>. Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai.

- ^ 日本刀の刀匠・刀工「無鑑査刀匠」. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Touken Earth.

- ^ Mason Smith (December 1997). "Stand and Deliver". Black Chugalug magazine. Active Interest Media, Inc. 35 (12): 66. ISSN 0277-3066.

- ^ Graham Priest; Damon Young (21 Baronial 2013). Martial Arts and Philosophy: Beating and Nothingness. Open Court. p. 209. ISBN978-0-8126-9723-0.

- ^ Thomas A. Dark-green; Joseph R. Svinth (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. ABC-CLIO. pp. 120–121. ISBN978-1-59884-243-two.

- ^ Gordon Warner; Donn F. Draeger (2005). Japanese Swordsmanship: Technique and Exercise. Boston, Massachusetts: Weatherhill. pp. 110–131. ISBN978-0834802360.

- ^ Almost martial arts sword cuts to ane mat (Suegiri) Guinness world records.com

- ^ Fastest 1,000 martial arts sword cuts [ permanent dead link ] Guinness world records.com

- ^ Most sword cuts to harbinger mats in three minutes Guinness earth records.com

- ^ Fastest tennis ball (820km/h) cut past sword Guinness globe records.jp (in Japanese)

- ^ "Virtually martial arts sword cuts in one infinitesimal (rice harbinger)". Guinness World Records. 25 June 2016. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019.

- ^ "South.I. No. 338/2009 — Firearms and offensive Weapons Act 1990 (offensive Weapons) (Amendment) Order 2009". Irish Statute Book, Government of Ireland. 28 August 2009.

- ^ The Criminal Justice Act 1988 (Offensive Weapons)(Amendment) Order 2008. Opsi.gov.uk (19 November 2010). Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- ^ "Ban on faux Samurai swords". BBC News. 12 December 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

Calls for a ban came after a number of loftier-profile incidents in which cheap Samurai-way swords had been used as a weapon. The Domicile Role estimates in that location take been some 80 attacks in recent years involving Samurai-style blades, leading to at to the lowest degree v deaths.

- ^ EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM TO THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE Act 1988 (OFFENSIVE WEAPONS) (Amendment No. 2): Society 2008. opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

Further reading [edit]

- Perrin, Noel (1980). Giving Up the Gun: Nihon'due south Reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879 . Boston: David R. Godine. p. 140. ISBN978-0-87773-184-9.

- Robinson, H. Russell (1969). Japanese Arms and Armor. New York: Crown Publishers Inc.

- Due south. Alexander Takeuchi (aka T). "Dr. T's 'Nihonto Random Thoughts' Page". Florence, AL: Department of Sociology, University of North Alabama. Archived from the original on 8 Jan 2010.

- Yumoto, John M (1958). The Samurai Sword: A Handbook. Boston: Tuttle Publishing. p. 204. ISBN978-0-8048-0509-4.

- Satō, Kanzan (1983). The Japanese Sword. Kodansha International. ISBN 9780870115622.

medeirosaftefuld66.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Katana

0 Response to "Heaven Sword and Dragon Sabre Read Online"

Postar um comentário